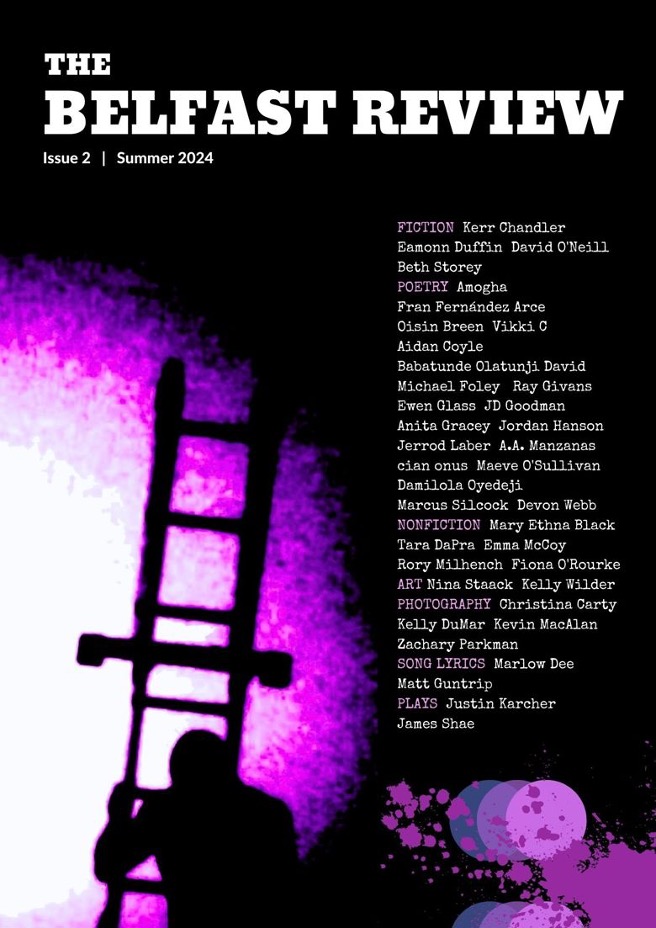

Published in the Belfast Review, Summer 2024, Issue 2

The rain swings in wide arcs. Thick rows of it slap the path outside your kitchen window making small prickles of water bounce off the concrete like rice,

like confetti.

The path is a large dance floor; each raindrop is both drumbeat and dancer. In this house, the window frames are warped from too many untreated winters and the kitchen is no different. Its handle is stubborn, wedged in the snug of heat beaten timber, and the force needed to open it will break it someday.

The sound of tapping raindrops fills the kitchen then.

You record a few seconds of video with your phone. It’s exciting, in a beige, domestic sort of way. And you drift, drift to shopping lists, to future conversations, to the things you might have said if your mind was sharp enough. These images, moving and soundless, are tiny, ferocious, one-act plays. Scenes roll behind a curtain of blurred vision. After a moment, you blink awake, your stomach ticking over as though covered with tarpaulin, a tiny drummer tapping their slow march. There is a half-empty coffee cup beside you, and you will have to leave for Tesco soon. Actually, it is more of a mug really, a Christmas mug, pale and dishwasher worn. Toby says to use porcelain, but you don’t have any of those. He would be disappointed, but there’s not much you can do about that, and there’s not really any way of him finding out.

You wonder if Tesco stock them anyway.

Gripping the worn-out Christmas mug with two hands, you pull the last of its warmth into your limbs and tap repeat on the song you had just been listening to. One more time. That should do it. Music fills the room and you drift slowly into a daydream, barely noticing it end. You weren’t listening properly. Once more. You will be ready to go then. Definitely.

A while later, you step outside. The door slips through your fingers, slamming loudly.

Stupid fuckin rain, you think.

Yeah, stupid fuckin hands more like it, you also think.

Ah now, come on. You were happy before, when you laid those very same hands out on the kitchen table right there through that window. Laid them out in front of him, palms turned upward on the Ikea oak, as open as an ocean, and told him that you wouldn’t be going anywhere without him. Didn’t you do that?

It was a symbol of passivity, of servitude, of devotion. And those hands weren’t so bad when you cradled him either, delicate as though he were made of silk. Didn’t you stitch the thread of yourself onto himself until you blurred so much that you couldn’t be told apart. Days would pass like diary entries, the world around you nothing but a dull echo, where it was impossible to tell if you had actually spoken at all, or if the words had been carried between you on some sort of current.

That was you, wasn’t it?

You wrote every word and every sigh into tiny little journals, kept tight to your chest like some holy book, when the howls and swirls of night seemed enough to keep the two of you wrapped up like a knot, and there was nowhere else for either of you to go, so you lay there, quiet and desperate.

It’s not those days anymore though.

You look up at a still angry sky. Dark veins streaking across the grey and, at a guess, you have around half an hour before getting properly soaked. Turning and walking towards the shops, your steps quicken. You tie your long hair into a bun and pull the hood of your coat over your head against the stiff wind. The material is heavy, curving across your field of vision. You tilt your head to see where you are going, an ear turned up to the stars like a curious dog. You tug the hood loose again.

A phone pings gently in your pocket.

Rachel.

You stand under a tree and scan the screen before angrily punching a quick reply to your sister. You know that if you don’t, she will turn up on your doorstep. You smile, or at least a thin, tight, approximation of one. The absolute worst thing about trying to kill yourself is all the attention you get when you make a balls of it. There is an obscene sort of irony in becoming a minor celebrity when the thing you wanted most was to get away from everything. Putting on headphones, you drop the phone back into your pocket.

In the condiment aisle you listen to Toby. A new podcast. You were looking forward to it, putting it off until you had the time to take it all in, but it’s disappointing. His voice doesn’t work in this medium.

The videos are better.

He’s talking about roasting styles with a British man you don’t know. The British man makes jokes about the aprons Toby wears in his videos, and it makes you smile a little because you can see them, clear in your mind, pastels, and patterns; each one linked to the theme of that week’s video. You started to watch Toby’s videos between the lockdowns. When you were still living together. When it was lopsided, and when people could easily be categorised and placed into clearly marked boxes labelled Good People and Bad People. If they stayed in, even when they were allowed to go anywhere they wanted, they were a Good Person. Being one of those meant that you cared about everyone, not just yourself. The way they reported it on the news, Good People seemed to care more than other people and they definitely cared more than Bad People. Those ones went out whenever they liked, and they drank in bars that let you stand way too close and they coughed and spat and kissed and fucked even though they probably shouldn’t have.

Standing under the harsh Tesco fluorescence, you think about yourself, and himself, and Toby, and what sort of person he was, back then.

I was a Good Person,

We were Good People.

We had stopped kissing by then too, so perhaps that made us Even Better People. Our very own category.

You would scan the fridge each morning before closing it again slowly. It was filled with goo that he said was alive, and it bubbled and spread so quickly that it popped the lids right off the jam jars he kept it in. See, at the time, people were trying to bake symmetrical bread and listen to bird song while trying to ignore the daily briefings, but bread was too difficult. He never got the hang of it and when you asked him when he was going to stop, he would only shrug like a tiny wave and afterwards, when he was back living with his Mam, he emailed you to say that it had only ever been a distraction, an excuse not to talk to you.

Anyway, none of this is about lockdowns, or bread. Nobody was any different in that regard. The real reason that you were a Good Person who did what she was told had nothing to do with choice. No. It was because all that passivity, and servitude, and devotion, had shrivelled to something that could be used as a weapon; something sharp, or hot, or explosive, whatever would inflict the most hurt.

Later, you tried to journal about it, another post-breakdown method of scouring the wreckage for survivors, but that was equally pointless. No matter how often you parsed through the fragments of it all, there was no moment, no time where things shattered, no loudness. Instead, it just dissolved.

As soon as the Government said that he was allowed to, he placed a small number of items in a cardboard box and got a taxi that would take him to Heuston Station. You presumed that he would be getting a train from there to Sligo, but destinations never came up and you felt that, by that stage, you couldn’t really ask.

Instead, you did a lot of pretending.

You pretended to read a book while he packed up his things and you pretended not to care when he tossed his key onto the couch beside you and you pretended that none of it was happening at all really, until the door closed and you threw a saucer at the closed wooden panel so hard it shattered like snow and you left the flakes of it on the floor for nine days until you stepped on them one morning and cursed him again. Rachel and Mam didn’t find out for weeks either. It was easy to avoid them when they were just text messages and Zoom links. They don’t exist anymore, you thought. Just binary code now. Everyone is a number.

When things eased off and people started going out again, someone tagged him in a photo, smiling happily in a Ballina pub. Slattery’s. You knew the place because he had brought you there when you first met his family. Though the photo was harsh and unflattering, his skin looked flash-white, and the background was a murky brown, you recognised it instantly. The table gave it away; lacquered plum with oval beer mats that reminded you of part-time shift work. The night you had been there together, you had the place to yourselves, save from the smattering of happy, round men that seemed content to let the cream from their pints sit on their grey moustaches. You felt that things had somehow changed then, that the past, and the lives you had lived before ever knowing each other, had now been completed, or that they now belonged to someone else. Between slow sips of your drinks, he had held your hand, and told you that you had done so well, and that the family all loved you like he loved you, and it had felt like you were both asleep then, curled around the complex glow of each other. As you walked back to his parents house you had cried, and when he asked what was wrong you made something up because the truth was that you were embarrassed by how much it had meant for you to be accepted.

Within an hour of the photo going online, Rachel was outside, her face unreadable. The sweeping force of her, gigantic and hot, filled your small kitchen and drowned out the laptop speakers. When she called, you were watching Toby explain how acid effects the balance and what small tweaks you could make to your machine to compensate for the diverging PH levels in each shot, but Rachel didn’t hear you, or she ignored you, you weren’t sure which. Instead, she told you that you looked like shit and when were you planning on telling anyone? and that Mam was now officially ‘up the walls’ with all of your carry on. As she spoke, you leaned against the back of a chair, feeling as though you might feint. Your stomach turned pirouettes on a tiny axis as the air and warmth drained from the room. Your throat collapsed clumsily, leaving you barren and hollow and your head tapped out a slow nod to her words, pausing only to cough or hmm after every second or third sentence but really, you can’t remember much else of what she said to you.

I don’t know.

It came out as if it were the only true statement left inside you.

I mean, all I know is that it happened, and he left, and here I am. What more do you want from me?

Rachel looked confused, so you repeated the question, your voice now waking into something blunt, a roar, and all of a sudden, this weight of knowing, and seeing the sucked-in judgmental faces of the other people that you were really saying those words to, made you double over with bright, hot tears. See, the only person that was making any sense was on mute in the corner of your kitchen, and all you wanted, more than anger and questioning and crying, was for Rachel to fuck completely off and mind her own business so you could continue watching your video about coffee.

*

You leave the shopping on the countertop and flip open the hinge of your laptop. You don’t watch the videos too often anymore, but you knew it had been a year to the day; sure, how couldn’t you? The thought that other people might also remember though, that was unsettling. That they had also put it in their calendar, or set discreet reminders on their phone, made you feel as though you had been blown open for anyone to casually inspect.

An exhibit.

Before you swallowed the pills, you laid them out on a table in your sitting room. You brushed them across the glass top for what seemed like an age before piling them high enough so that they looked like a mountain. After, you posted a rambling message on Facebook and a fireman kicked your door in and when you woke up in the hospital bed you couldn’t speak because your throat was scraped raw from the harsh plastic tube they used to empty your stomach. You were horrified to wake, but in the small window buried inside your chest there was a flicker of something, a quick dart of dopamine because there were might still be people in the world that cared for you.

Even so, you are disappointed that Rachel remembered. After a year, with the layers of filament and memory that get laid over everything like dust, you hoped that you could be allowed to roll along quietly, to keep this anniversary for yourself.

Earlier, standing in a queue as the rain battered the large windows of the supermarket giving them a blurred, opaque feel, you had thought about the other hospital, the one you were driven to by your mother, after the mountain of pills and the fireman. With the crisp whiteness of walls, and sheets, and uniforms, it felt as though you might have died after all. You sneered at its nakedness, how embarrassing it seemed, this perfunctory space that was supposed to make people want to live.

Only, despite yourself, it began to make sense.

Along with the reaching, expectant arms of spring, thoughts began to creep through the window you sat at most mornings. The white, in its clean, unflinching openness, helped you to notice things, new things. You noticed the cheerful flowers that reflected sunlight onto the ward walls. You noticed the deep ripeness of fruit that was left in shared spaces. You noticed the way staff members spoke with a musicality that bounced and soared compared to the wretched stillness of the patient’s voices.

In the months that spooled from your discharge, you laid claims on various new lives. You tried all the tricks they gave you, followed every guideline. Be creative, they said, so you did what came easiest, what you were fluent in.

You wrote with a pen.

You doodled.

You wrote about being unable to write.

Free association.

You searched online for tips and read blogs about writer’s block. You gave it all a go and it came to the grand sum of fuck all. Exasperated, you gave up and decided that from now on, cooking would be your creative medium. You tried to make art by shaving carrots into soups and grinding mustard seeds into deep, yellow powders. Unfortunately, you were too clumsy for culinary arts too, so you gave that up.

With your laptop open, you feel your phone ping in your pocket. Rachel, again. You choose to ignore it this time, prioritise yourself. The rain is beating heavier now, drumming against the window. You click into YouTube and search for the muscle memory of lockdown, of coffee, of Toby. You laugh at the thought that you would ever be so emotionally moved by a soft-spoken Korean man with a ponytail. You open the first suggested video,

Aesthetic Morning Brew.

Taking the coffee beans from your shopping bag, you feel a charge run through you. Hello there, coffee lovers, he says in his thin, angular voice.

Toby is excited, and his excitement rubs off on you. As you measure beans onto a digital scale, you are excited together.

You and Cafetière_Toby_Seoul.

Coffee buds.